Can We Save the Hammerhead Sharks of Cocos, Galapagos and Malpelo?

^^T^^he Eastern Pacific has more than its share of Earth’s most spectacular marine life and diving encounters. At its core is the Golden Triangle: Costa Rica’s Cocos, Colombia’s Malpelo and Ecuador’s Galapagos. The names of these islands rightly evoke images of sheer underwater magnificence: big shoals of big fish, including jacks, barracudas and tunas. Megafauna, from the only place yet discovered where large, pregnant whale sharks gather. Earth’s largest aggregations of tropical dolphins. Famous schools of hammerheads and silky sharks. The key area for huge and growing jumbo squid populations. Breeding and feeding grounds for blue, sperm and humpback whales. For big-animal encounters, particularly schooling sharks, there probably is nowhere else on Earth where divers can encounter these kinds of numbers.

"I’m holding the rocks, scanning for hammerheads. Walls of fish block my view. I know that hammers are shy, so I stay at the edge, just outside a cleaning station. Out in the blue, they come. Not dozens, hundreds. I slow my breathing and move forward. They are coming in waves, a pulsing wall of hammerheads passing just a couple of yards away. Magnificent.” — Damien Mauric, underwater photographer

It’s an exciting time, as scientists begin to unlock the secrets of the region and the movements of its charismatic giants through deep water and along its chains of seamounts.

Exciting, but tempered by concerns brought by this same burgeoning understanding. Tagging of large animals and a better appreciation of the area’s seasons and ecology are giving us insight into how this region works. We know more now about the migrations of large ocean travelers between these island and seamount hot spots. Hammerheads and other sharks use these areas for rest and socializing, heading out and away at night to feed, with some animals moving between sites with the seasons.

But as migrating animals move away from and between these islands, they move out of protected areas — and toward an unknown fate.

Damien MauricImmense aggregations of jacks are a hallmark of Cocos, now under threat from illegal and unsustainable fishing.

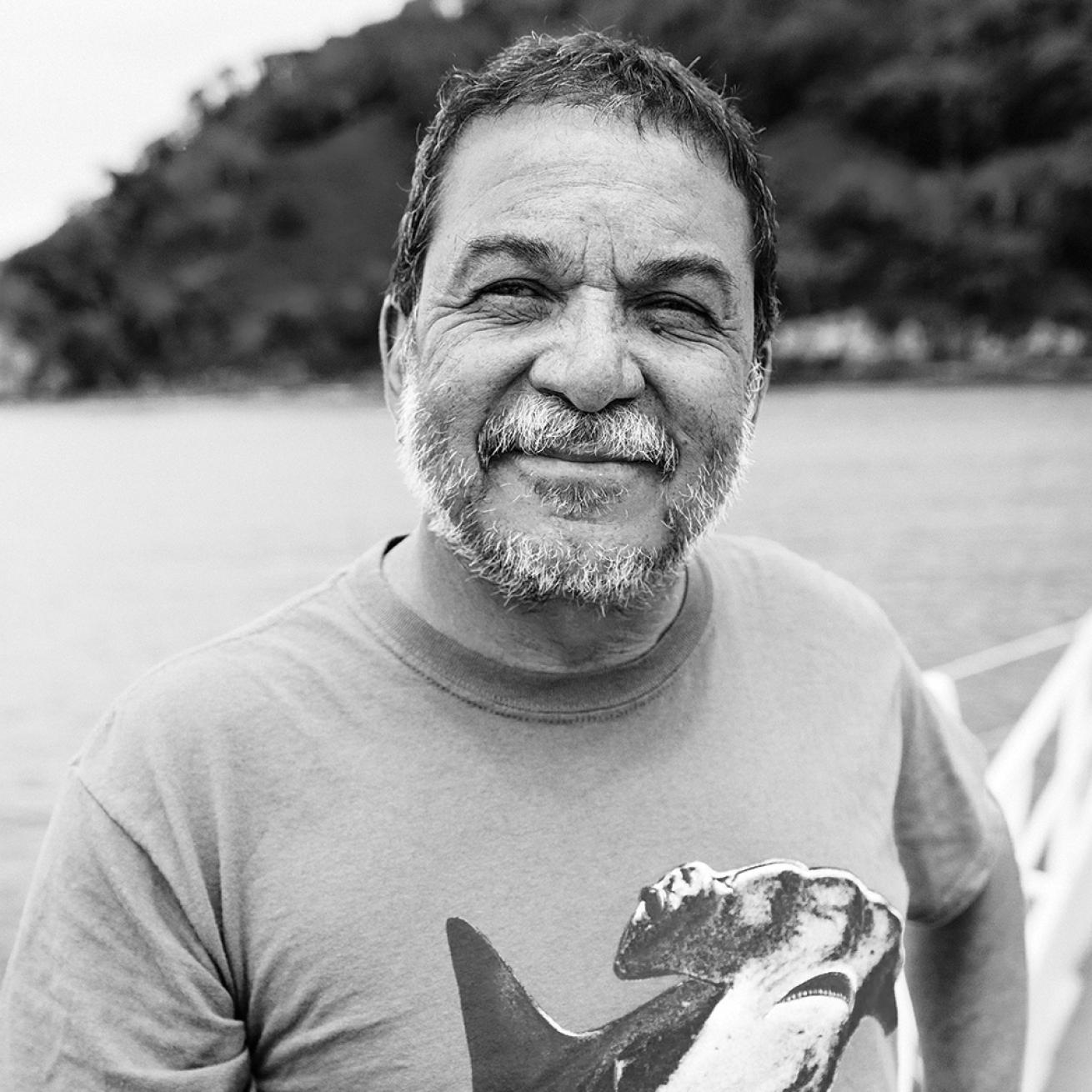

One Angry, Passionate Man

^^R^^andall Arauz is a passionate, smart, dedicated man — and these days sometimes an angry and frustrated one. He’s been involved in Cocos Island research and conservation since 2004, with 36 trips to the island as a marine scientist, tagging sharks and turtles, and using submarines to place acoustic receivers on local seamounts.

Damien MauricRandall Arauz

Several hundred sharks and turtles, and smaller numbers of manta rays, have been tagged to date across the region. The whale sharks and some of the silkies have so far been the champion long-distance migrators, some spanning right across from the Galapagos, Malpelo and Cocos to Baja, the Revillagigedos and Clipperton Island to the north, and Peru to the south.

Hammerheads prefer the core of the Golden Triangle — a dozen hammers tagged at Cocos have made trips to Malpelo and the Galapagos, but many more regularly shuttle between Cocos and Las Gemelas, or the Twins, seamounts 40 miles away along the Cocos ridge that forms a highway to the Galapagos. Scientists call the ridge — used as a migration route from Costa Rica to the Galapagos by green and leatherback turtles as well as by Galapagos, hammerhead and silky sharks — the Galapagos-Cocos Swimway. It’s a well-used route — and perhaps the most important bridge for marine animals between the Costa Rica Dome and Humboldt-Galapagos ecosystems.

Research carried out by Arauz and other scientists has led to the implementation and expansion of a marine-protected area and a no-take zone, now extending 400 square miles to include Las Gemelas. Arauz and conservationists across the region have formed Migramar, a coalition of scientists and conservationists building a solid base of understanding on migration corridors and seamounts, and the movements of sharks, turtles and cetaceans through the region. They have used this understanding, and the science underpinning it, to advise and, in some cases, lobby governments to protect these areas and conserve their megafauna.

Damien Mauric(Clockwise from left) Eagle rays are a frequent sight; hammers are much more shy, and tend to stick to cleaning stations like this one at Manuelita Deep; coral also is under threat at Cocos, from climate change and predation.

Costa Rica’s government, however, currently seems more supportive of short-term fishing than conservation. You can sense the frustration in Arauz as he catalogs the slow, steady weakening of protection of Cocos from fishing. Since 2014, hammerheads have been listed under CITES; to export their fins requires studies demonstrating that the fishery is sustainable.

"Alcyone seamount is always special, discovered and named by Jacques Cousteau after a boat my grandfather designed for him. Alcyone is arguably Cocos’ diving highlight; hammerheads can form a wall of hundreds of sharks from far below divers to the surface.” — Damien Mauric

In 2014, the government allowed the export of more than 2,000 pounds of fins, but then acknowledged that shark fins should not have been exported until a council of scientists could demonstrate sustainability.

Scientists recommended maintaining the ban on shark-fin export, so the government has changed who can sit on the council — twice. The government recently reduced the committee to a single scientist and several members of the industrial-fishing industry, apparently in the hope that they can get a body that tells them it is sustainable to export fins.

While discussions continue, shark fishing continues, with fishing companies simply stockpiling the fins until they can bypass or change the council’s recommendations.

Costa Rica Thermal Dome

Damien MauricA Galapagos hogfish defends hidden eggs. When the Costa Rica Thermal Dome rises, it brings an explosion of marine life.

The large-scale ecology of this region is driven by the interplay of two vast, rich ecosystems: the Costa Rica Thermal Dome north of the equator and the Humboldt-Galapagos system that reaches from South America and spreads along the equator. These systems are two of only three areas on Earth — the other being in the northwest Indian Ocean — where extensive cold-water upwellings bring an abundance of marine life to the open oceans of the tropics. Tropical seas in general are virtual deserts, but where these cool-water systems approach the surface, plankton erupts, and millions of ocean giants feed on trillions of prey animals over several thousand square miles. As the sun moves north and south with the seasons, these two giant systems — particularly the CRTD to the north — shift, expand, and contract with the ebb and flow of the seasons.

The CRTD is a bulge of deep, cold, nutrient-rich water between 100 and 200 miles across, depending on time of year, pulled up from the depths to just a few yards below the surface. When it rises, it brings an explosion of life. Cocos Island — about 5 miles long by a little over 2 miles wide, 340 miles off Costa Rica — is at the southern edge of the CRTD through the middle of the year.

Unlike other islands of the eastern tropical Pacific, Cocos is lush and green. Hammerhead numbers at Cocos may be the highest in the world. From May through September, hammerheads, whale sharks and mantas reach their highest numbers around the island.

Life With Sharks

^^S^^andra Bessudo first came to Malpelo in 1987 and was bowled over by the schools of silkies and hammerheads.

She also noticed several fishing boats moored to reefs, with sharks on board. This was the start of a life dedicated to the conservation of Malpelo. Beginning with a petition — and small numbers of mostly friends, divers and conservationists — Fundacion Malpelo was created in 1989.

A chance meeting served her well. While doing research, Bessudo inadvertently entered a military zone on Colombia’s Caribbean side; the navy boat that intercepted her had on board then-President Cesar Gavaria. She told him that if he truly loved diving, he should go to Malpelo.

Mauricio AngelSandra Bessudo

Gavaria had never heard of Malpelo; Bessudo ended up guiding him for a day of diving there. A year later, Malpelo was declared a sanctuary — 3,310 square miles were protected in 1995. The Colombian navy now works with Colombia’s National Parks Authority to organize annual scientific expeditions to the island. Because the navy boats are dedicated primarily to fighting drug trafficking, it takes a little work and negotiation to get their time and support; since 2000, there has been a real scientific program in place thanks to Fundacion Malpelo.

Fundacion Malpelo’s goals and roles are to raise funds to study and protect Malpelo, which the foundation co-manages with the National Parks Authority. The funds are used to support the science program, evaluating migrations between the islands of the Golden Triangle.

The foundation also promotes Malpelo as a sanctuary and diving destination, both within Colombia and with international visitors, and renews mooring sites around the island. Divers booking trips through Fundacion Malpelo make a small contribution via the boat operator. The foundation is currently raising funds for a catamaran to monitor the area around the island.

Damien MauricLa Ferreteria (left) is a site where moray eels also seem to “school” reliably in big groups. Silky sharks school in large numbers — a star attraction at Malpelo — at a site called Sahara (right).

Since Malpelo became a marine park, most species have shown signs of recovery, although hammerheads are still decreasing at a dramatic rate. Silkies have rebounded in recent years, by the thousands, although Bessudo now sees hundreds with hooks embedded in their mouths.

Colombia was the first country to implement legislation banning the landing of shark fins, and directed shark fishing is now banned. (Bycatch of sharks is not illegal, but the entire shark must be landed, with fins attached.)

"As we get close to stop depths, a single shark cruises by, followed by a dozen more. Soon we are drifting in a school of hundreds of silkies. They are not as shy as hammerheads and seem intrigued by my fins — every time I turn around, I can see five or six curious sharks very close behind me. I don’t want this dive to end.” — Damien Mauric

After six years of lobbying, a law was passed in July 2017 to fight illegal fishing and poaching. Until this law, the navy had 30 hours to bring suspects to the nearest port for prosecution. This worked for drug traffickers but not for Malpelo poachers — Malpelo is 40 hours by boat from the nearest Colombian port. Today, the 30-hour deadline starts once the poaching boats arrive in port.

The government has increased the size of the marine protected area to more than 10,000 square miles, and the navy now patrols the MPA, actively chasing and arresting poachers.

Since the law was passed, one boat has been seized. Since then, no illegal vessels have been seen in the area. Bessudo believes that the Colombian authorities have the willingness and the teeth to fight illegal fishing.

The Oasis of Malpelo

Farther inshore than the Costa Rica Dome or the Galapagos, Malpelo sits in relatively warm, nutrient-poor seas between these two vast productive zones. Even tinier than Cocos, at less than a mile long and a third of a mile wide, Malpelo is a magnet to silky and hammerhead sharks. Only the island breaks the surface, but its submarine ridge is extensive.

At a little more than 300 miles offshore, Malpelo is close enough to the coast to benefit from upwellings that run along the ridge with the Panama Current, enriching the seas for the first few months of the year, which bring the greatest numbers of hammerheads. The seasonal offshore Panama Current, and its position between the two great systems, allows Malpelo to act as a steppingstone, an oasis between the great northern and southern ecosystems.

A handful of hammerheads tagged at Malpelo early in the year have been seen just a few days later off the Galapagos, more than 600 miles away, and several migrated from Malpelo to Cocos. Later in the year, the number of resident hammerheads at Malpelo drops, leaving the Dome and Galapagos systems more isolated.

Thinking Bigger

^^C^^ésar Peñaherrera has spent the past decade tagging megafauna and studying population dynamics and ecosystems, trying to understand and quantify the benefits of marine protected areas.

Tuna fisheries — the major local fishery — outside protected areas have improved their catches in the whole of Ecuador with the creation of the Galapagos MPA.

William GiraldoWilliam Giraldo

For sharks, the results have been more mixed. “The MPA works for species that aggregate locally, but not ones that migrate outside” — notably the hammerheads, Peñaherrera explains. As in Cocos and Malpelo, hammerheads are the worst impacted of the megafauna, Peñaherrera says. “Their numbers have halved — they are not doing great. They move away from the MPA and can be fished elsewhere.”

Peñaherrera, the academic director of Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador who leads biological data collection and analysis at Migramar, believes that Galapagos’ larger number of islands helps protect aggregation sites compared to Cocos’ MPA. (Cocos’ system of seamounts would also need to be covered to provide that same level of protection.)

Peñaherrera is building a foundation of scientific data to help governments make informed decisions on building larger MPAs. In general, the industrial-fishing fleets in Ecuador understand that MPAs will boost their business long-term and allow fish populations to grow. But smaller, artisanal fishing operations live day to day, and don’t necessarily take a big-picture view.

Damien MauricResearchers believe the Galapagos’ MPA offers better protection to megafauna such as whale sharks because of its larger size; hammerhead sharks are not faring well in any of the Golden Triangle’s protected areas.

Peñaherrera says that fisheries are still by far the greatest threat to the marine megafauna of the region. For years it’s been known to the diving community that fishing vessels wait for nightfall at the edge of the Galapagos Marine Reserve’s 40-mile boundary. When patrols or visiting liveaboards are out of the area, they move in. Fishing vessels — either illegally or with the compliance of authorities and fisheries patrol agencies — are longlining through national parks and other protected areas, and hitting the famous shark schools hard.

"Our dive is coming to an end. It’s been incredible — hammerheads everywhere, trevallies in the thousands. I find it hard to tear myself away. I reach safety-stop depth, and out of nowhere comes a bus-size whale shark. It passes through and leaves us behind, far too brief an encounter.” — Damien Mauric

With large MPAs, Peñaherrera expects a certain amount of illegal fishing will persist. But as destructive as fishing can be to Galapagos’ megafauna, there might be worse to come.

Peñaherrera and Migramar have tracked turtles and other animals heading farther west and north from the islands, following jellyfish aggregations and finding themselves in the great Pacific garbage patch. Plastic clogging the stomachs of megafauna is one thing; microplastics is a more insidious and larger problem, working its way in through the bottom of the food web. “It’s a huge issue, and in the midterm, it’s going to be the largest threat,” Peñaherrera says.

Like Bessudo in Malpelo and Arauz in Cocos, Peñaherrera is a believer in dive tourism as a strong support for conservation in the Triangle. It’s a revenue-producing alternative to fishing, and the economic gains from dive tourism last longer. The pressure to fish, though, comes back again and again — the battle today is for exposure and awareness, and it’s not won yet.

The Galapagos Ecosystem

Damien MauricThe islands' endemic marine iguanas need warm seas to breed.

The Galapagos ecosystem is an offshore, tropical continuation of the Humboldt Current system that runs up from Antarctica and feeds the western coast of South America. Chilean and Peruvian waters historically supported the largest fisheries on Earth along the edge of their continental shelves, and the southern Ecuadorian shelves are similarly rich. The Galapagos extension of this system, more than 500 miles west of the mainland, sees the same waters heading straight out to the west more than 600 miles farther along the equator, pulling up rich, cool water and nutrients with them, supporting a marine ecosystem almost as rich and productive — and more consistent throughout the year — than the Costa Rica Dome. Much of the megafauna migrates between the Galapagos and the Ecuadorian and Peruvian coasts, where the chilly, green waters provide even more food.

From December to March, the seas around the Galapagos are a little warmer. This brings the greatest numbers of hammerheads to the area, famously around Wolf and Darwin islands. The warmth also seems to be appreciated by the islands’ marine iguanas, which breed during the warm season, as well as by schooling mobula rays.

Through the middle of the year, the Galapagos system cools, and plankton productivity increases. The large whale sharks that Wolf and Darwin islands are renowned for gather in numbers, periodically heading out to feed or perhaps to give birth in deeper water westward along the equator.