Tests and Limitations for Diving after Heart Surgery | Heart Disease & Diving Chapter 5

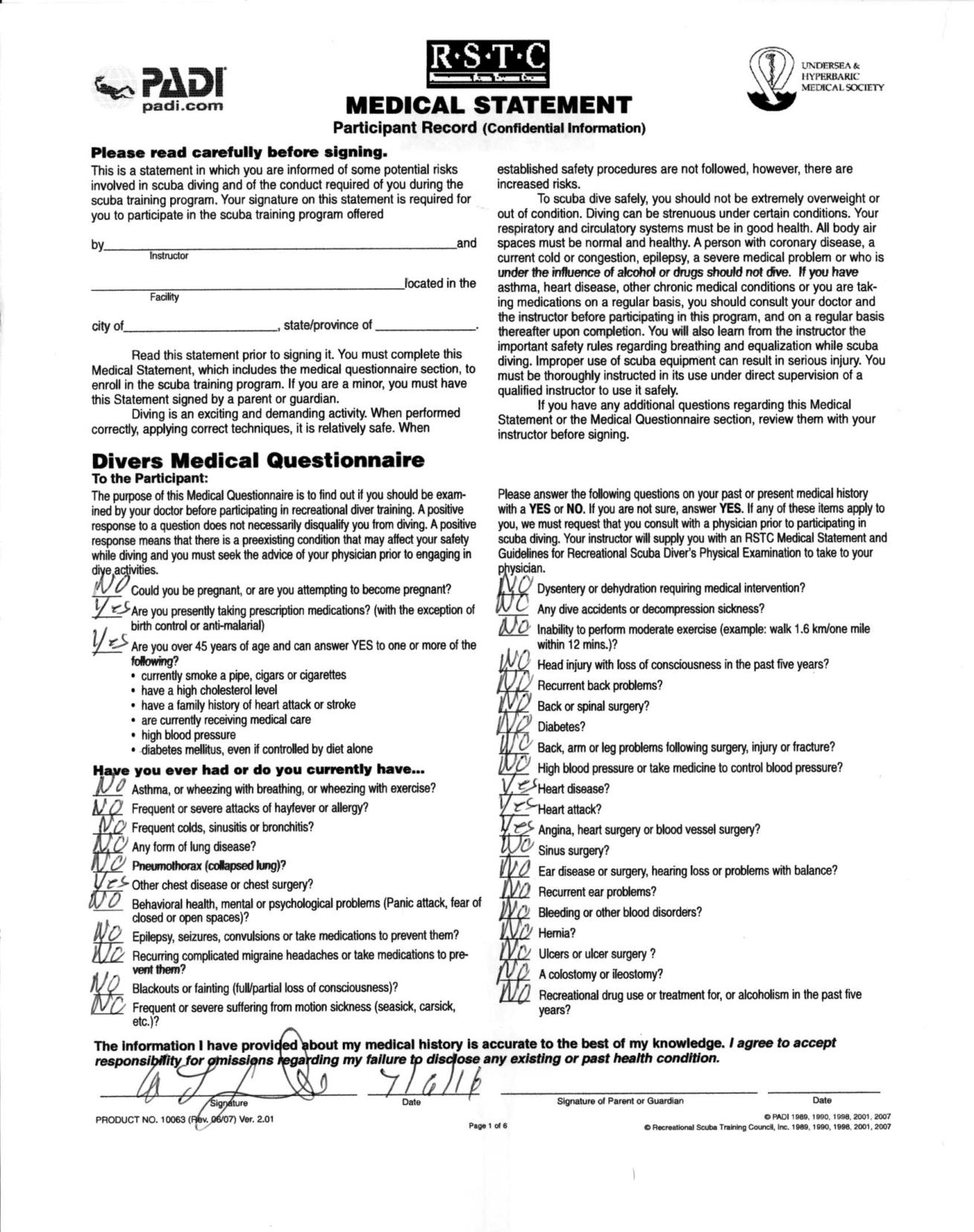

Courtesy Eric DouglasWhen filling out his medical form to scuba dive, Eric Douglas must now share that he has had a heart condition and provide a letter of approval from his doctor.

Chapter 5: Passing the Heart Test

I’ve previously written about the importance of telling the truth on your medical form when you sign up for a class or register to go out on a charter boat Ask an Expert: Revealing Medications. During the interviews, a few people I polled said they found the medical forms invasive, but just about everyone else thought they were important to ensure the safety of both divers and the dive operations.

Every year, dive fatalities occur after a diver lies on his medical form (and yes, it is usually men) and then suffers a fatal heart attack during the dive. More than one of these have shown up in the Lessons for Life columns.

I bring all of this up because, since January 2016, I have gone from being able to write “No” on all of the questions on my medical forms to having to provide dive operators with a letter from my cardiologist. Of course, with big scar down the center of my chest, it would be nearly impossible to hide the fact that I’ve had open-heart surgery.

To understand what all of this means to me as a diver, I went back to the Diving Doctor James L. Caruso, M.D.

“Once a diver has been treated for severe ischemic heart disease, whether it is with bypass surgery or coronary artery stents, the decision to return to the active diver roster must be individualized. If there has been damage to the heart or if surgical intervention [bypass surgery] has occurred, there will be a period of time for cardiac rehabilitation. If coronary bypass surgery has taken place, the risk of air getting trapped in the lungs and/or chest cavities is increased above baseline. This stems from breaching the chest cavity during surgery and the adhesions that result from surgical intervention. Stents placed in the coronary arteries are less problematic. The chest wall is not breached for the placement of stents. However, in both approaches to revascularizing the heart, typically some disease of the coronary arteries remains. And it is not unusual for an individual to develop new blockages or develop blockages within the grafts or stents.

“The diver should complete this rehabilitation and work up to a level of unrestricted activity without any symptoms (chest pain, shortness of breath, numbness or tingling in the extremities, light-headedness). The diver’s progress through cardiac rehabilitation will most likely be followed with periodic treadmill-EKG testing. For someone to be able to safely return to diving, he/she should be able to sustain a fairly high level of activity (jog or even slow run) without experiencing any symptoms that may be related to cardiac ischemia.”

“If there is any doubt about the success of the procedure or how open the coronary arteries are, the individual should refrain from diving.”

Now that I have successfully completed cardiac rehab, I am focusing my exercise regimen on being able to pass an EKG stress test and return to dive status. In an article Caruso wrote for Divers Alert Network called “Cardiovascular Fitness and Diving”, he says:

“After a period of healing — six to 12 months is recommended — an individual should undergo a thorough cardiovascular evaluation, which includes an exercise stress test. The individual should perform at a level of 13 mets (stage 4 on Bruce protocol). This is a fairly brisk level of exercise, equating to progressively running faster until the patient reaches a pace that is slightly faster than running an 8-minute mile (for a very brief period of time). Performance at that level without symptoms or EKG changes indicates normal exercise tolerance.

“If there is any doubt about the success of the procedure or how open the coronary arteries are, the individual should refrain from diving.”

Caruso mentioned the Bruce Protocol, which is a standardized diagnostic test developed by Robert A. Bruce that monitors cardiac function during exercise. Each stage of the Bruce Protocol is three minutes. The stages are:

| STAGE | TREADMILL SPEED | TREADMILL INCLINE |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | 1.7 mph | 10% |

| Stage 2 | 2.5 mph | 12% |

| Stage 3 | 3.4 mph | 14% |

| Stage 4 | 4.2 mph | 16% |

The percentages reflect an incline on the treadmill deck. A 16-percent grade is pretty steep. Achieving Stage 4 is my goal, but it is important to understand that it takes different amounts of energy to achieve 13 Mets of exercise depending on your body weight. “One metabolic equivalent (MET) is defined as the amount of oxygen consumed while sitting at rest.” That said, regardless of your weight, 13 Mets is tough. There is a complex formula for determining Met outputs, but there are dozens of online calculators. Unless you are really into algebraic math and are studying exercise physiology, I would use those.

When I started researching what it would take me to get back underwater, my reaction was filled with a fair number of words that can’t be uttered on primetime network television. Having been on a lot of dive boats, I have my doubts that most divers could achieve Stage 4. I asked Caruso about that.

“While there appears to be a higher bar set for a diver with known heart disease, it really isn’t the case. It would be ideal if all divers had a sufficiently high level of fitness to function well in the underwater environment, even in emergency situations. There are thousands of divers out there with undiagnosed cardiovascular problems who would benefit by screening tests for coronary artery disease. Each year the DAN diving fatality database is populated with a few dozen diving related deaths that are attributed to heart disease. However, once a diver has been identified as having significant cardiovascular disease, the medically responsible approach is to set some fitness expectations and make recommendations that reduce the risk of sustaining another cardiac event not only while diving but at any time.”

In other words, according to the medical community, all divers should be able to function at this level, but the only ones forced to are the ones who have known heart disease. That makes sense, and I can live with it. My interpretation is that more of my fellow divers should be exercising a bit more and eating cheeseburgers a bit less.

But what about restrictions? I’ve heard of doctor-ordered depth limitations given to divers who’ve had open-heart surgery.

“There really is no physiological basis for setting depth limits for a diver with heart disease. This is probably more a lack of understanding of diving physiology on the part of the physician. It is probably not a bad idea to at least encourage more conservative diving for individuals with known prior cardiac issues. They will likely not have the same cardiac reserve to safely get out of emergency situations should they occur. However, setting a strict depth limit is probably not necessary. It is possible that the recommendation is based on the fact that should a diver develop a problem at depth, getting up from a deep depth or out of a cave will be much more complicated and take considerably more time than aborting a 40-FSW open-water dive.”

Writing this series, I have spoken with a fair number of people who have had heart disease and been able to return to diving, as well as a people who are still in the process. Since the day after I returned from the hospital, I’ve exercised at some level nearly every day with the goal of getting back in the water in mind. I haven’t received permission from my doctor yet, but I hope to have that soon. Even if it takes you three years, keep working. You’ll make it happen.

Now, it’s time to go jump back on the treadmill. My next stop, hopefully, is to jump into the water.

Missed something? Here are the previous installments from Eric Douglas on his road to recovery.

Chapter 1: First Signs of Heart Disease

Chapter 2: What You Learn During the Cardiac Rehab Process

Chapter 3: How to Make Heart-Healthy Changes

Chapter 4: What are the Risks of Diving after a Heart Attack?

Author’s Note:

Since 2009, I’ve written the Lessons for Life column for Scuba Diving magazine providing analysis of scuba diving accidents so others can learn from them — and hopefully avoid being in the same situation.

In the ultimate Lessons for Life, I invite you to follow along as I write about my personal experience with coronary artery disease, open heart surgery and the recovery process over the next few months.

Eric Douglas co-authored the book Scuba Diving Safety and has written a series of adventure novels, children’s books and short stories — all with an ocean and scuba diving theme. Follow him on Facebook or check out his website at booksbyeric.com