A Wreck Like No Other: Diving Into the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Alabama Historical CommissionKamau Sadiki preparing to dive on the Clotilda shipwreck.

It’s tempting to mistake maritime archeology as simply researching shipwrecks while scuba diving.

“You can see it like that, but you’re missing the story,” says Kamau Sadiki, lead instructor and board member of Diving With a Purpose. “Each one of these vessels has a very powerful and tremendous story to tell. The only way that you can tell that is to interrogate it, to investigate it, feel it, sense it.”

Diving With a Purpose

Alabama Historical CommissionKamau Sadiki entering the Mobile River to dive the Clotilda shipwreck.

Diving With a Purpose (DWP) is a non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation and protection of submerged heritage resources, with a special focus on understanding and interpreting ships involved in the African slave trade. Through his work with DWP, Sadiki found himself in Mobile, Alabama, exploring the wreckage of an infamous slave ship. “When I was diving on the Clotilda–I have to pause for a moment because every time I remember it, it brings back a lot of energy, a lot of emotions,” Sadiki says, holding back tears.

To fully understand the immensity of this work, one must trace through wrecks, historical records and oral histories. This is what DWP, along with its partner historians and archeologists, do to reconstruct the stories behind shipwrecks.

Related Reading: Youth Diving With a Purpose

The History of Clotilda

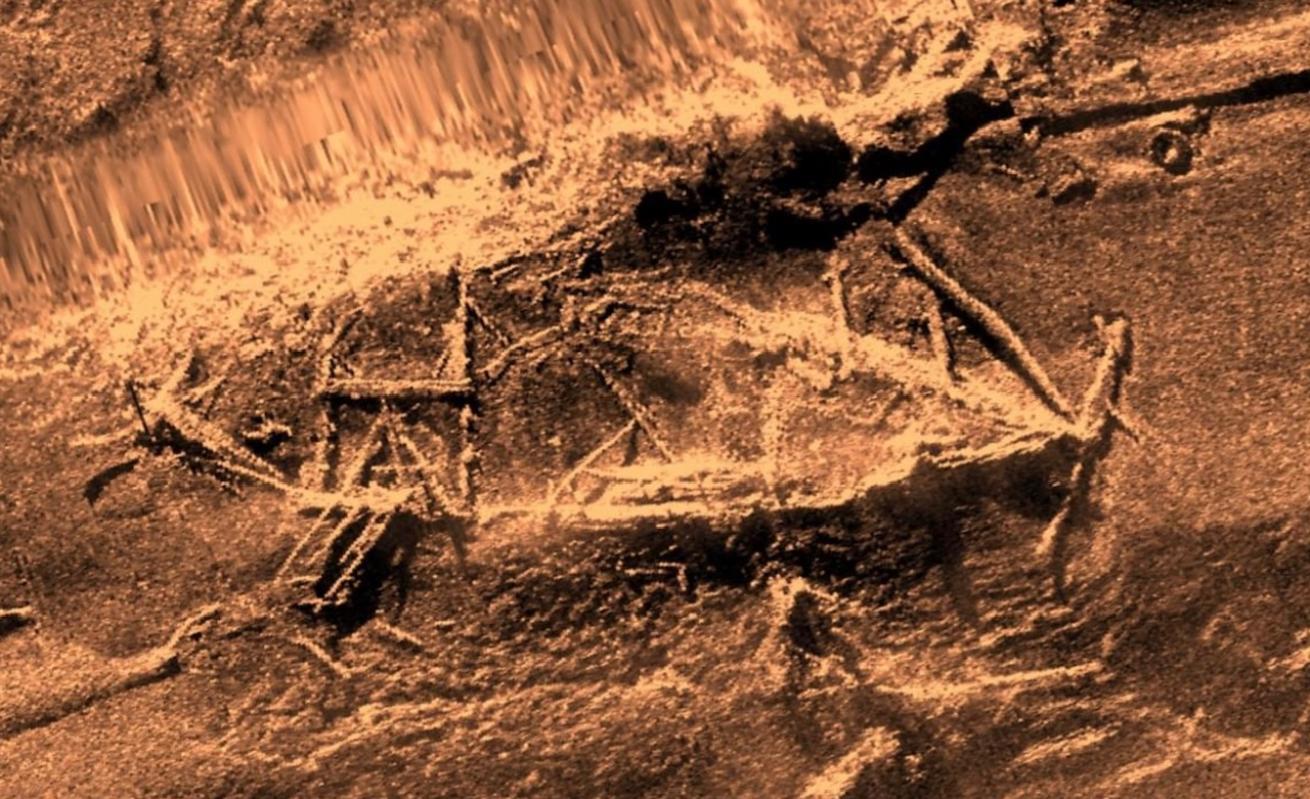

In 1860, the schooner Clotilda sank in the murky waters of the Mobile River. The U.S. had banned the importation of slaves in 1808, yet decades later, southern plantation owners still demanded slaves to work cotton fields. Clotilda illegally transported 110 people from modern-day Benin in West Africa to Mobile, Alabama. Upon arrival, the captives were unloaded, and the ship was burned and sunk to conceal the crime.

Alabama Historical CommissionSide-scan sonar image of the Clotilda in the Mobile River.

Five years later, in 1865, the 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the United States. Juneteenth commemorates June 19 in that same year, when federal troops took control of the state of Texas to ensure the emancipation of all enslaved people.

Alabama Historical CommissionKamau Sadiki preparing to dive on the Clotilda shipwreck.

The Clotilda captives saved money to start their own community in this new land, one which endures today as Africatown, in southern Alabama. As for the ship itself, Clotilda became the last known slave ship to enter the United States, and historians searched for her wreckage until she was finally discovered in 2019.

Diving into the Past

In that same year, Sadiki braced himself before entering Clotilda. This is the only known slave ship where the actual hull of the ship still exists, he explained. All the others have been broken up or destroyed, but nearly 80% of Clotilda’s structure remains.

Visibility was “virtually zero,” and the veteran diver had to “listen with [his] hands, see how it feels” as he traced his way along the hull. “Like braille diving,” he adds. When they reached the bulkhead, he paused. “On the other side is where the captives were held … I said, ‘Oh wow, I’m here. Shall I go in or shall I not? If I want to hear them, I have to go in.’”

The them of course, are the 110 souls known to have been captive on Clotilda. Sadiki entered the ship alone.

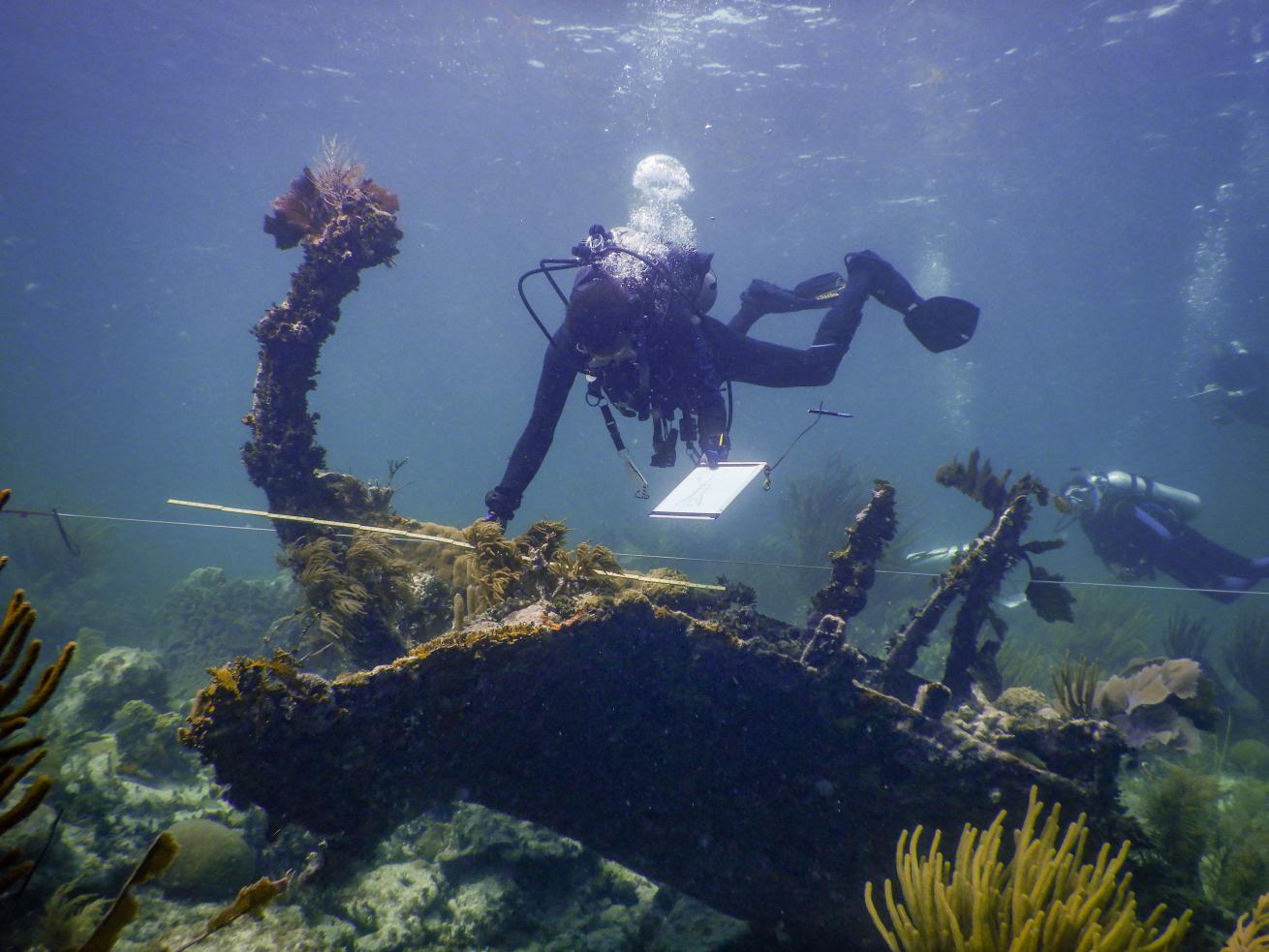

Ocean Rebels/Tiffany DuongKamau Sadiki helps document a shipwreck in the Florida Keys unrelated to the slave trade. His drawing will be added to a site map that tells the story of the wreckage.

“As soon as I went over the gunwale–the wall of the ship–and went inside, I began to tumble,” he recounts. “There was no current, and I consider myself a pretty good scuba diver with over 1,400 dives, right? So I begin to tumble, and I somehow righted myself and–I’m not trying to be esoteric or anything–I feel this real embrace, warm embrace.”

The water temperature was a cool 75°F, and Sadiki continued sifting through decades of sediment and muck with his hands. He continues, “I was just feeling the walls and the sides where these people had touched. Where they had weeped, where they had cried, where they had all their bodily functions and so forth. It was a very, very humbling, powerful, emotional experience for me.”

Related Reading: Ken Stewart Honored as a Scuba Diving Sea Hero

Ocean Rebels/Tiffany DuongDWP instructors, divers and trainees map a wreck in the Florida Keys in 2022.

“The forced maritime relocation of enslaved Africans to the Americas is one of the most influential events in world history, but only limited archaeological research has been done on the subject,” says Matthew Lawrence, a maritime archeologist with the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries who works with DWP in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. “Archaeology provides a means to learn about the lives of past peoples through the things they made and left behind. Oftentimes this information sheds light on people's lives who are not recorded in the history books because they were poor, marginalized or lived lives outside of centralized societal constructs.”

Sadiki believes that the 12-15 million people who were taken involuntarily as part of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, who had their voices silenced by history, are now speaking through DWP’s divers. The science and the data collected are one dimension of this work, Sadiki emphasizes; feeling the energy, suffering and pain that reverberates when he touches an artifact, that’s another very powerful, very important dimension.

“I will never ever forget that moment in my diving career,” Sadiki concludes. “It’s indelible now, I won’t ever forget it.”