Diving RMS Rhone in the Shadow of a Storm

“ONE, TWO, THREE, GO!” I press my palm to my regulator and back-roll off the tender. The divemaster, Michael, hands me my camera—a red, many-armed, glassy-eyed device that is beginning to resemble an octopus. I dump the air from my BCD and drop below the surface into the azure quiet surrounding Salt Island. Visibility is good in spite of the recent storm—I can see both the sandy bottom 40 feet below and our dive guide, Capt. Shea, though he’s particularly hard to miss, kitted out in bright-pink shorts, long freediving fins, and a green shirt with an enormous cartoon character on it. The pointer stick he carries prompts us in the direction of the prize we are seeking—the wreck of RMS Rhone.

I am apprehensive, not because the dive itself is challenging, but because this is one of the most iconic wreck dives in the Caribbean; it has a reputation to uphold. Not only was the Rhone featured in the 1977 film The Deep, but its tragic and untimely demise is the stuff of legend.

As we draw close to infamous Black Rock Point, the scenery changes. Sand becomes rock, and reef life ripples into view—tube sponges and parrotfish, feather duster worms and damselfish—an explosion of color on an otherwise somber debris field. Soon I make out the shadowy skeleton of the stern, tucked into the dark rock that rises above it like a tombstone. I pause and hold my breath. The Rhone is a living museum, a battered piece of history whose gnarled innards are now exposed to my curiosity.

Although 155 years separate us, I feel a strange kinship with this ship and its crew, having weathered a powerful storm myself just before embarking on my trip aboard BVI Aggressor.

See also: How to Pack for a Liveaboard Dive Trip (The Complete Packing List)

History (Not Quite) Repeated

Candice LandauThe author’s Cessna is prepared for departure to Tortola in Puerto Rico, luggage stowed up front to balance the onboard weight of just two people.

A few days before my flight departed for the British Virgin Islands, a depression formed in the Atlantic. Twenty-four hours later it was given a name: Tropical Storm Fiona. Worst of all, her path was set to coincide with mine, right over the Island of Tortola, where I would shortly be based.

I wrote to Aggressor Adventures and asked if my liveaboard trip would still proceed as planned. They assured me they were in constant communication with the captain, who was actively assessing the situation. As any practiced diver does, I swallowed my fear and focused on what I could control—chronicling the journey. And so, just like RMS Rhone, I headed into the impending storm. Fortunately, I had a much more pleasant outcome.

The First "Unsinkable" British Ship

In 1867, veteran sailor Capt. Frederick Woolley assumed command of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company’s (RMSP) prize ship, RMS Rhone. A feat of modern engineering, it was built from iron rather than wood and boasted a powerful steam engine and screw propeller. Even at 310 feet long, four decks high, and with a carrying capacity of 313 passengers, it could cover ground fast.

Setting sail from Southampton, England, Woolley’s first voyage aboard Rhone took just 12 days. When he arrived on the island of St. Thomas, he was met with a sight that filled him with dread—a harbor full of ships from every corner of the world. A breeding ground for illness.

See also: History of the BVI's Rhone Shipwreck

Wikimedia CommonsThe steamship RMS Rhone and its smaller counterpart, Solent, anchored at port in St. Thomas, circa 1865.

At the time, yellow fever was a deadly epidemic thought to spread via direct and indirect physical contact. Attempting to limit exposure for his passengers and crew, Woolley decided to refuel instead at nearby Peter Island.

What he did not realize was that in trying to avoid one disaster, he unwittingly put himself on track to meet with another.

Days later, stationed at Peter Island, Rhone made a routine exchange of passengers and cargo with two other Royal Mail Steamers—Solent and Conway. The exchange took place under gray skies and gusting wind. Not liking the look of things, Woolley prepared his crew to move to Beef Island, just off Tortola.

Both he and the captain of Conway believed this the safest place to ride out a storm. The captain of Solent disagreed, surmising that they were dealing with a hurricane and not a northerly. He decided to drop anchor 1.5 miles from Peter Island—neither too close nor too far from land.

Conway began its move into the open Sir Francis Drake Channel, and Rhone prepared for a similar move. Unfortunately, the storm hit sooner than expected. Now in unsheltered waters, Conway was struck by the full force of what was indeed a hurricane, tossed about as if nothing more than a leaf in the wind.

Rhone, still anchored just a few hundred yards from land, had a worse problem—the anchor chain had broken. The only option left was to head for open ocean, far from land and reef.

Then, just as suddenly as the storm came on, it abated. The sky cleared and the sun shone through. It was a chilling moment—they were in the eye of a hurricane, the most dangerous place to be.

Within half an hour, the raging winds and rain were back. In spite of stoking furnaces and doing everything possible to make haste, they were too close to land. The dark mass of Black Rock Point loomed ahead, and with a sickening boom, Rhone made contact. Once, twice, thrice. When the boiler exploded, the ship began to break in two and seawater seeped in. Within minutes, Woolley had been washed overboard alongside most of his crew. Ten minutes after impact, the great unsinkable Rhone had sunk.

Of the 145 people on board that night, just 25 survived, only one of them a passenger. Most of the survivors were washed ashore clinging to debris. The captain’s body was never found. Both Conway and Solent made it through, though each suffered extraordinary structural damage. It was a storm to remember.

See also: Wreck Diving on the Rhone in the British Virgin Islands

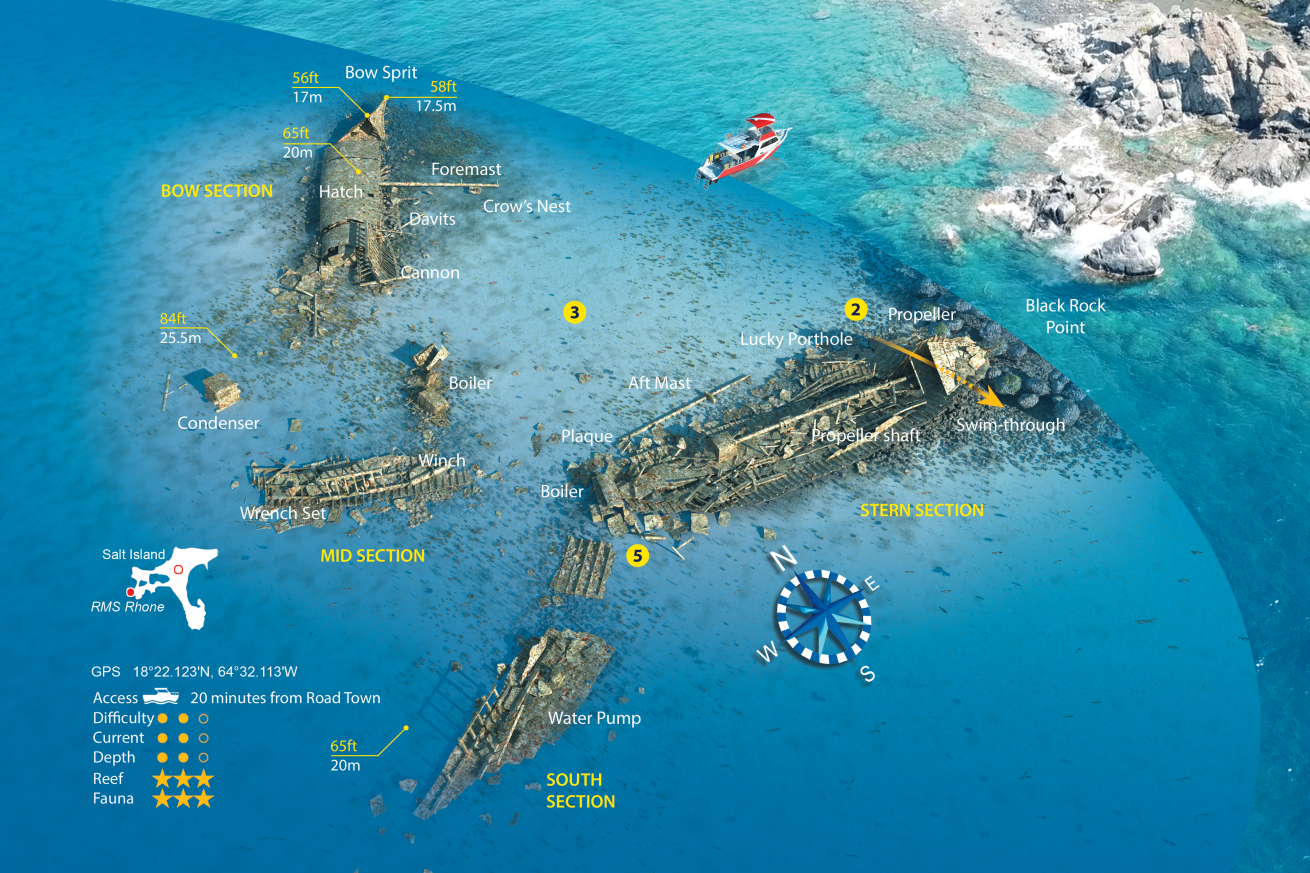

Reef Smart GuidesA detailed map of the RMS Rhone wreck provided courtesy of Ian Popple and Reef Smart Guides—this waterproof dive guide is available for purchase online at reefsmartguides.com

A Nail-Biting Buildup

When I reach Puerto Rico—the first leg of my journey—the airport staff warn me that if Fiona hits they may lose power. Following one of them onto a runway as gray as the sky, I wonder if I’m insane. Am I flying out only to be trapped in a hotel room on Tortola as a hurricane approaches, or worse, on a heaving sea? It’s too late though; they’ve loaded my luggage into a beat-up Cessna 402C, the pilot and I the only souls on board. I feel like a war correspondent heading to the front lines.

Candice LandauCaptain Shea and Captain Casey discuss heading out after the storm.

Over the course of the next few days, both the island and I prepare for the worst. Road Town closes its shops, sandbags its doors and pulls all outdoor furniture inside. The airport and the ferry terminal close too. I blast through my land-based touring and double down on my rum purchases at Callwood Distillery.

Rain and wind come in fits and starts. My weather app is both optimistic and inaccurate, pushing back the storm’s arrival time every few minutes.

When I finally board BVI Aggressor, I am anxious to know our plans. Capt. Shea is there to greet me. A broad-shouldered man with blond hair, blue eyes and an air of calm friendliness, he tells me we will be spending a couple of nights in Road Town’s harbor—our hurricane hole. Steadied by two long mooring lines, we will ride out the storm and await the other passengers currently stuck in Puerto Rico. With four spacious decks, it’s a much bigger boat than I thought it would be.

Portents of the recent past dot the still-beautiful harbor—wrecked sailing boats and battered buildings, piles of damaged cars. Even as I try not to concentrate on these remains, I am aware that the face of this hilly island is different today than it was in 2017 before Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 storm, devastated the Virgin Islands.

In the end, all the trepidation is for naught. Fiona skirts past BVI, and clear skies and blue waters return as my dive trip truly begins. We’re late, and I’m excited, not to mention relieved, to be diving the Rhone rather than experiencing a storm as it did.

Diving the Legend

For our first dive on the Rhone, Jim briefs the site. He’s the best sort of dive guide: free of ego, a good listener, a marine biologist, and a natural comedian.

With the help of a whiteboard illustration, he walks us through the stern and midsection. He calls our attention to three things: the last remaining portion of the ballroom dance floor, the lucky porthole, and the wrench set and winch.

Now, submerged 40 feet below the surface, I glimpse a square of checkered floor tiles. When the captain holds out his hand I immediately know what I’m looking at. I smile through my regulator and place my hand in his. He twirls me in a circle.

Luis Javier SandovalThe author and a school of squirrelfish captured sheltering behind the Rhone by BVI Aggressor photographer Luis Javier Sandoval.

We continue our exploration, and my attention flits from mast to plaque to empty porthole. Shea ducks into the swim-through and a skittish nurse shark slithers over the sand below him. Mesmerized, I snap a couple of pictures before turning to inspect this small dark cavern. The roof bursts with color—corals, anemones and small crustaceans, delicate hydroids and beautiful, spotted flamingo tongue cowries. Off to my right, a school of tiny fish glitters like a crystal chandelier. Shea points out the huge propeller.

Everywhere I look a piece of Rhone’s history slots into place. The rocks behind the stern, its death knell. The last intact porthole, a glimpse into what was once Cabin 26. Were I a better wreck detective I’d rattle off a list of the various parts I see. As it is, a blanket of fire coral obscures much of the finer detail.

Back on board BVI Aggressor, I am treated to one of Jason’s decadent meals. My vegetarian diet is no problem for this creative chef-cum-divemaster as he whips up flavorful concoctions that have even the staunchest meat lovers putting in a request for whatever it is I’m eating.

Javi briefs our next dive. A talented photographer, he has been hired by Aggressor to document our adventures. He also has his own quirky sense of humor, a love of good buoyancy and a unique ability to both act and scold underwater.

Luis Javier SandovalAn iconic scene on a piece of the RMS Rhone.

The bow of the Rhone is even more impressive than its stern. It’s immense, parts of it rising like Grecian columns. As I inspect the sponges, sea fans and tunicates that cover these metal ribs, Javi has me pause. He takes a few pictures and then guides the rest of the group toward the foremast and the bowsprit. I am last to arrive. The others are gathered in a circle surrounding a porcupinefish the size of a cat. Its huge doe eyes watch us all and it drifts calmly from person to person, completely unfazed. Javi gets our attention and then dramatically mimes biting his finger. I look upon the fi sh with newfound respect, fingers curled tightly out of sight.

The bow has a swim-through larger even than the one on the stern. Multiple people can fit comfortably inside it. I turn my flashlight on and peer into the many twisted crevices. Shrimp and arrow crabs peer back. Brittle stars slip for cover wherever my beam exposes them.

At the end of the dive, Javi has us pose near a school of vivid red squirrelfish. Normally shy, these fish don’t veer away. They wait patiently for our photographer to get the shot he wants.

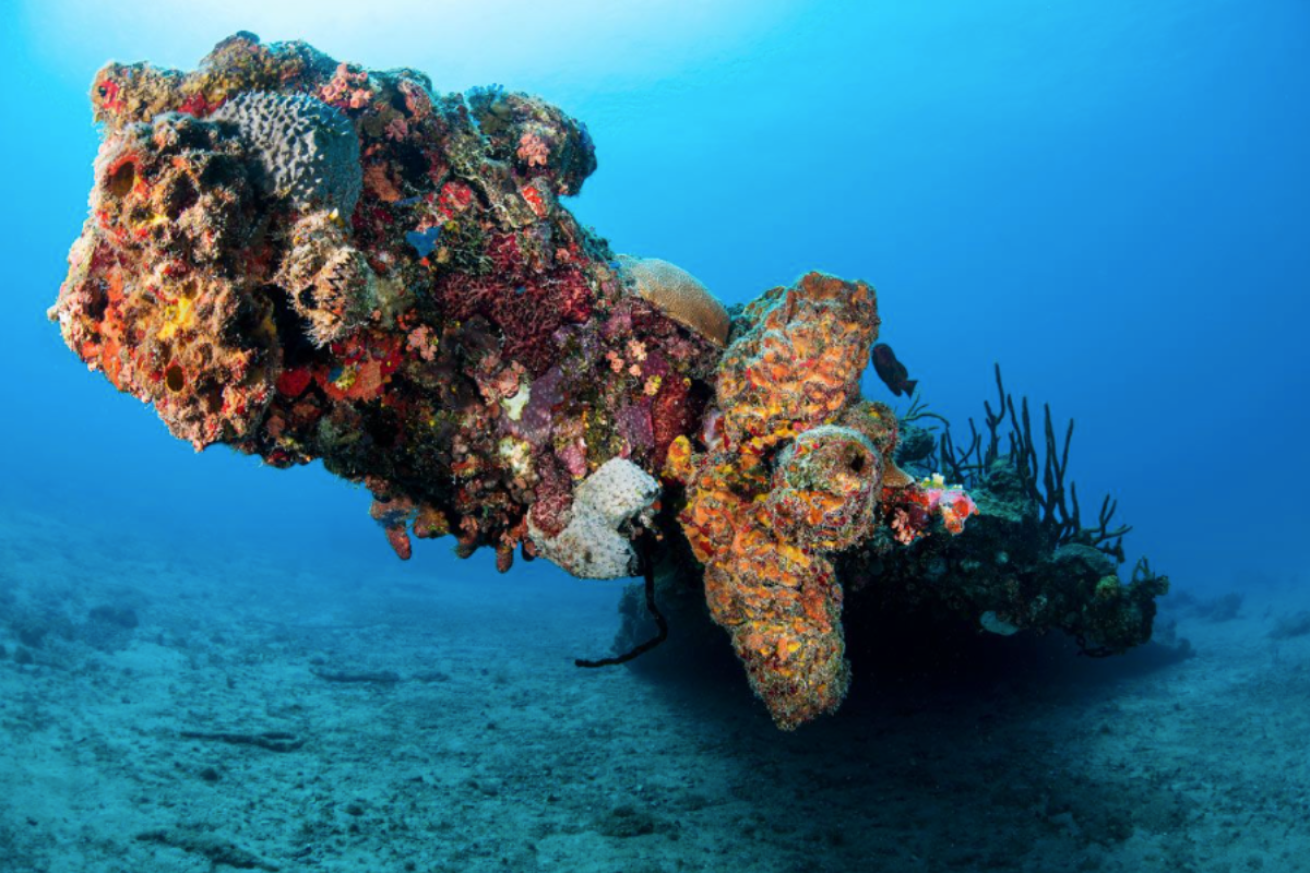

Jeff Yonover/Imagequestmarine.comThe bowsprit of the RMS Rhone has had more than 150 years to become a coral-encrusted fish magnet.

Later, we return for a night dive, our final dive on this glorious wreck. Shea attempts to point out every critter he can, but I am so overwhelmed by the water column right in front of me that I can’t concentrate on the various eels he is gesturing to. Blood worms and transparent siphonophores and ctenophores, salps, pyrosomes and all manner of other black-water diving critters bombard me. They dance in the dark; they rush up against my hands and my face. They defy capture on my camera screen. When I finally see past them, it’s the basket stars that hold my attention. Enormous balls of writhing legs—invisible in the day, active at night.

On our ascent a shoal of small squid is present. They hover nearby and then with torpedo-like accuracy, they bomb us, one after the other, brown ink spreading like spilled coffee in the surrounding water. I am astonished. I can feel the punches. It doesn’t hurt, but it’s not something I’d choose to endure for more than a couple of minutes.

When we finally clamber back on board BVI Aggressor, my fellow South African ex-pats, co-Capt. Casey and nightwatch Dale are there to greet me with a cup of hot chocolate and Baileys. Matt, the interim engineer, smiles and holds out a fresh towel. I warm my hands against my mug and settle into the unexpectedly beautiful night—star-studded, hurricane-free, and culturally rich. This is an adventure I could live on repeat.

Courtesy Aggressor AdventuresBVI Aggressor and tender boat.

Need to Know

Operator: Aggressor Adventures

Conditions: Water temperatures average 82–84°F in the summer months and 76–78°F in the winter months. Visibility can range from 30 feet to more than 100 feet depending on weather and water conditions.

When to visit: While hurricane season in the Caribbean is from June to November, the British Virgin Islands are still considered a year-round destination. The author’s trip took place in September 2022.

What to wear: Most guests make as many as five dives each day, so some thermal protection is needed. A 1 to 3 mm wetsuit or shorty is recommended year-round. However, some people prefer a 5 mm in January and February.

Getting there: Most people choose to fly to Terrance B. Lettsome International Airport (EIS) on Tortola and take a ferry to Road Town, where the boat is stationed. Other options include a ferry from Puerto Rico.

Where to stay: Because the yacht is docked at the harbor in Road Town, it is recommended to pick a nearby hotel for logistical ease. The Village Cay Hotel and Marina is a favorite for guests.

Fees: BVI Aggressor charges a port fee of $95 per person (seven nights) or $135 per person (10 nights), and a fuel surcharge of $150 per person at the end of the week. There are no required fees for entering BVI.

The author’s favorite dives on BVI Aggressor: RMS Rhone, Kodiak Queen, Willy T, Coral Gardens, and Spyglass Wall.

Topside Attractions

Candice LandauA photography of Callwood Distillery from the outside.

Callwood Distillery: Over 200 years old, this distillery offers some of the best rum tasting in the Caribbean—unique flavors, and quirky beverage names. The historical building also houses the longest continually running copper pot in the Caribbean.

Road Town: A great place to shop, eat and use as a base. Consider visiting Tortola Pier Park, Pusser’s Road Town Pub, the Watering Hole, Island Roots, J.R. O’Neal Botanic Gardens, Fort Burt, and Her Majesty’s Prison Museum.

Candice LandauBVI Aggressor Instructor Jim poses at the Baths.

The Baths: Huge granite boulders create natural cathedrals and caves you can walk through, snorkel and clamber at this geologically unique beach on Virgin Gorda. Access this national park by boat or a short shore hike.

Candice LandauA view of Cane Garden Bay from the road above.

Cane Garden Bay: This popular beach lined with bars and restaurants is a great place to snorkel or relax with a drink. Try the Painkiller cocktail, a local favorite.