Unprecedented Mass-Bleaching and Significant Coral Mortality in the Florida Keys

Coral Restoration FoundationA dead elkhorn coral on Sombrero Reef has white (bleached) and orange (tissue slough, which is dead coral tissue killed by the heat).

“This makes me feel really sad. It’s honestly really depressing–gut-wrenching, heartbreaking, soul-breaking kinda stuff,” said Andrew Ibarra, a NOAA-Affiliate marine stewardship and monitoring specialist for the Mission: Iconic Reefs (MIR) project in the Florida Keys.

Ibarra and many coral restoration practitioners, scuba divers and ocean lovers have taken to social media in the last few weeks to bring awareness to what’s happening on the Florida Reef Tract: a coral mass-bleaching event on a scale never before experienced.

What’s causing this catastrophe? Heat, and lots of it.

Water temperatures in the Florida Keys have been higher than average since February of this year. Mid-July’s water temperatures were 1°C - 3˚C warmer than usual, noted a MIR factsheet. In fact, last week’s South Florida sea temperatures were 35°C–the warmest on record since recordings began in 1981. For comparison, the average temperature during this time of year should be 23°C - 31°C. Critically, the optimal temperature range for Florida’s reef-building corals is 23°C - 29°C, and even 1°C rise in temperature can cause bleaching, the factsheet said.

Related Reading: Keys to The Florida Keys

While mild bleaching has occurred in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS) annually for the last five years, this year’s marine heatwave has led to widespread mass bleaching that is happening too soon and too fast. A majority of corals–regardless of whether wild, restored or in coral nurseries–are in various stages of paling, fluorescing, bleaching and dying.

Andrew IbarraA Colpophyllia natans colony on June 10 and July 23. The coral is already dead, and algae (fuzzy brown, yellow) has started to grow over the skeleton. The soft coral growing behind it on the right is full and healthy in the before shot and withered away, dead in the after.

Under normal conditions, healthy corals contain symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae that live within their tissues, providing the typical orange-brown coral color divers are used to seeing and also 90% of their host corals’ energy needs. However, heat-stressed corals will often kick out their zooxanthellae, resulting in a “bleached” whitish look. Bleaching doesn’t always cause coral death, but if adverse environmental conditions persist, or if bleaching events are prolonged or happen too frequently, “significant coral mortality can occur, sealing the fate of coral reefs,” UNEP reported. Heat stress also makes corals more susceptible to diseases, and “high levels of disease” have been observed on many Florida reefs, the MIR fact sheet reported.

Ibarra has been documenting Cheeca Reef, a shallow Florida Keys reef that normally boasts an astounding 25-30% coral cover. He said, “All I saw underwater was a field of white. Every coral of every colony of every species had been bleached. Cheeca has coral colonies out there that are decades, even centuries old. To see them totally bleached out and/or recently killed made me very angry, sad, upset–really, a mix of emotions.”

Related Reading: Pristine Coral Reef Untouched by Bleaching Discovered in Tahiti

Andrew IbarraA recently-dead elkhorn coral at Horseshoe Reef. Algae has not had a chance to overtake the skeleton.

The July 28 BleachWatch Current Conditions Report listed an “Alert Level 2” with “significant bleaching expected; mortality likely” for corals. In a somber written statement, Coral Restoration Foundation (CRF) reported the “unimaginable – 100% coral mortality” on Sombrero Reef, a site the nonprofit has been restoring for over a decade, and the loss of almost all corals in their Looe Key Nursery. MIR seafloor sensors measured Sombrero and Looe, both renowned reefs for divers, as two of the hottest reefs, with the former clocking in at 32°C and the latter at 34.1°C.

CRF and other Keys restoration organizations are now “rescuing” and relocating as many corals as possible from ocean nurseries to land-based holding systems or to deeper water.

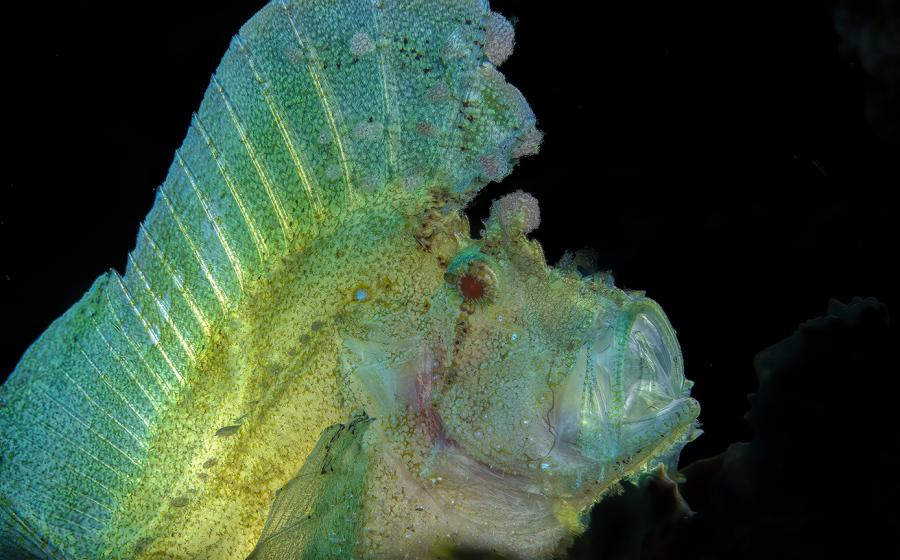

Beyond corals, the marine heatwave is also causing an ecological cascade. Ibarra described soft corals and sponges that were “bleached or evaporated–wisps of what they used to be.”

dcb9.jpg?itok=6mq2oFXx)

Will BensonMany small, tropical fish overheated and died in the unprecedented marine heat wave.

Additionally, gorgonians, fish, seagrasses and other marine life are overheating and/or suffocating. Paddlers and boat captains reported fish kills and disintegrating sponges nearshore as well as offshore. “All plants and animals need oxygen to live,” explained Florida Wildlife Commission’s program administrator Tom Matthews, and hotter water holds less oxygen. It also fuels harmful algae blooms and increases microbes and bacteria in the water–both of which further decrease oxygen levels and degrade water quality. This year’s extreme temperatures have caused oxygen levels to decline lower than the levels needed by many species to live, Matthews said.

So, how bad will it get?

Nobody knows for sure. The critical factor is how long high temperatures persist. If they subside, bleached corals might recover. Unfortunately, August and September are normally the hottest months in the Keys, and some predict catastrophic heat through October.

Related Reading: Ocean Warming Could Lead to Smaller Fish, New Study Finds

Ibarra said, “For the majority of corals across the reefs, we’re still in bleach phase. They’re bleached, but still alive…. But, if this weather continues for the next four to eight weeks, throughout the summer, there’s a real chance we could be calling this a mass mortality in a month or two.”

Experts in Action

Coral restoration practitioners continue to survey the damage done by the hot water. Some report deeper, offshore reefs still holding on with healthy, non-bleached corals. Most practitioners have moved important coral genotypes from ocean nurseries into temperature-controlled land-based facilities. In these survivors, there's still hope, they emphasize.